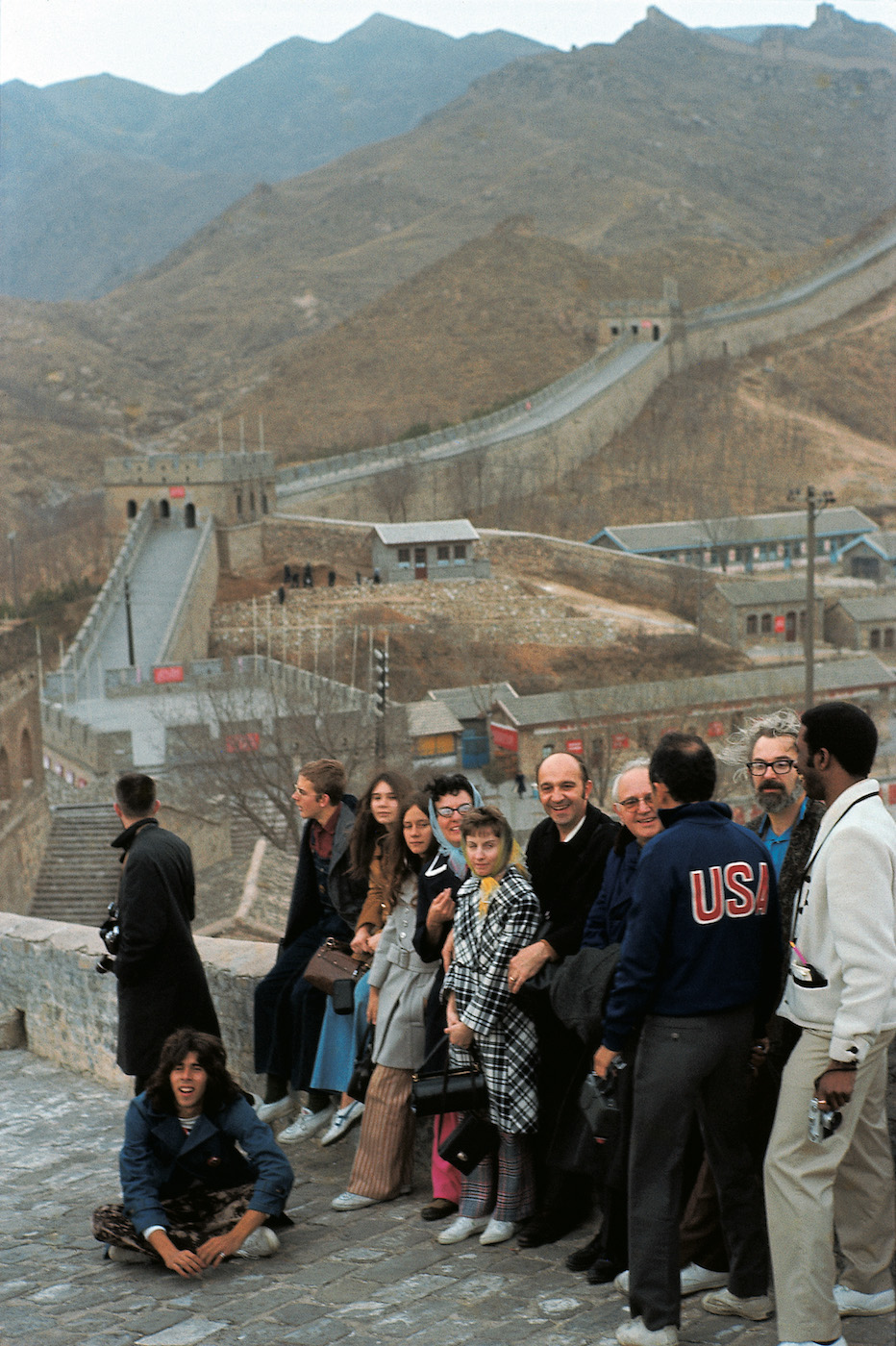

In the late 1960s, banned from South Africa, Frank Fischbeck joined LIFE magazine in its Hong Kong bureau. The city was an ideal base from which to “China-watch”. One of these occurred in April 1971, with the beginning of what was nicknamed “ping-pong diplomacy”. It involved actual table-tennis; but the real match was being played out between Mao Tse-tung, leader of China, and Richard Nixon, president of the United States. As Frank was fortuitously based in Hong Kong, this amazing assignment fell into his lap.

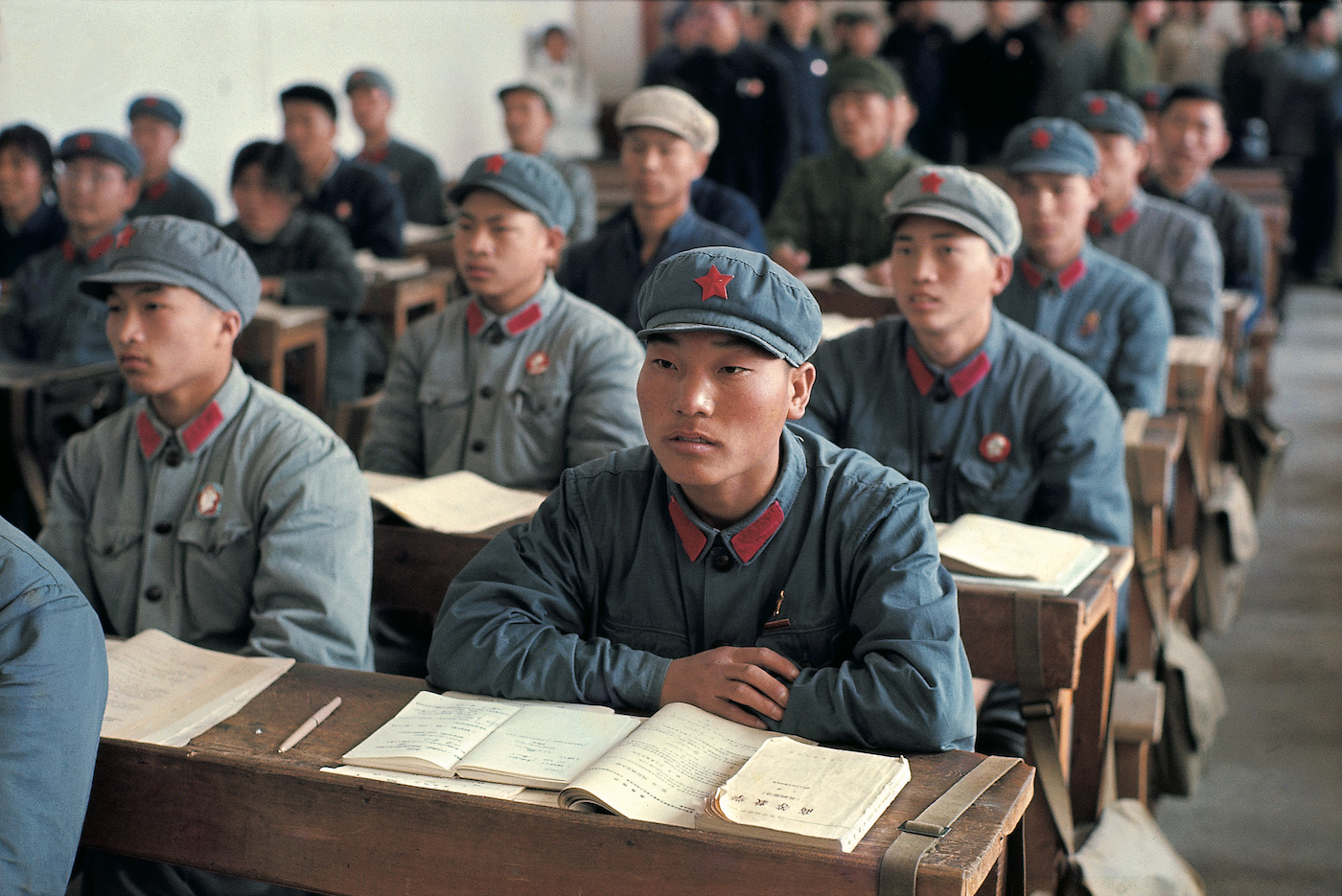

The opening serve was unexpected. China, mostly sealed-off from the West for two decades, had invited Great Britain, Canada, Colombia and Nigeria to compete in table-tennis matches in Beijing and Shanghai. A week beforehand, that invitation was surprisingly extended to the United States. With that, China the greatest mystery of the 20th century was emerging from the worst excesses of its Cultural Revolution and nobody outside its metaphorical ‘bamboo curtain’ knew quite what to expect. Having deliberately kept itself immured, China was ready for a – carefully managed – close encounter.

And it sought global attention. Previously impossible to obtain visas were quickly granted to America’s most influential media, including LIFE magazine. Frank and LIFE’s Far East Bureau Chief, John Saar, were handed the extraordinary eight-day assignment. Frank was the only professional photographer to cover the United States team. LIFE’s issue of 20 April 1971 had one of his memorable images on the cover; more filled the 21-page coverage inside. “The best look the U.S. has had at China in 20 years,” stated the magazine