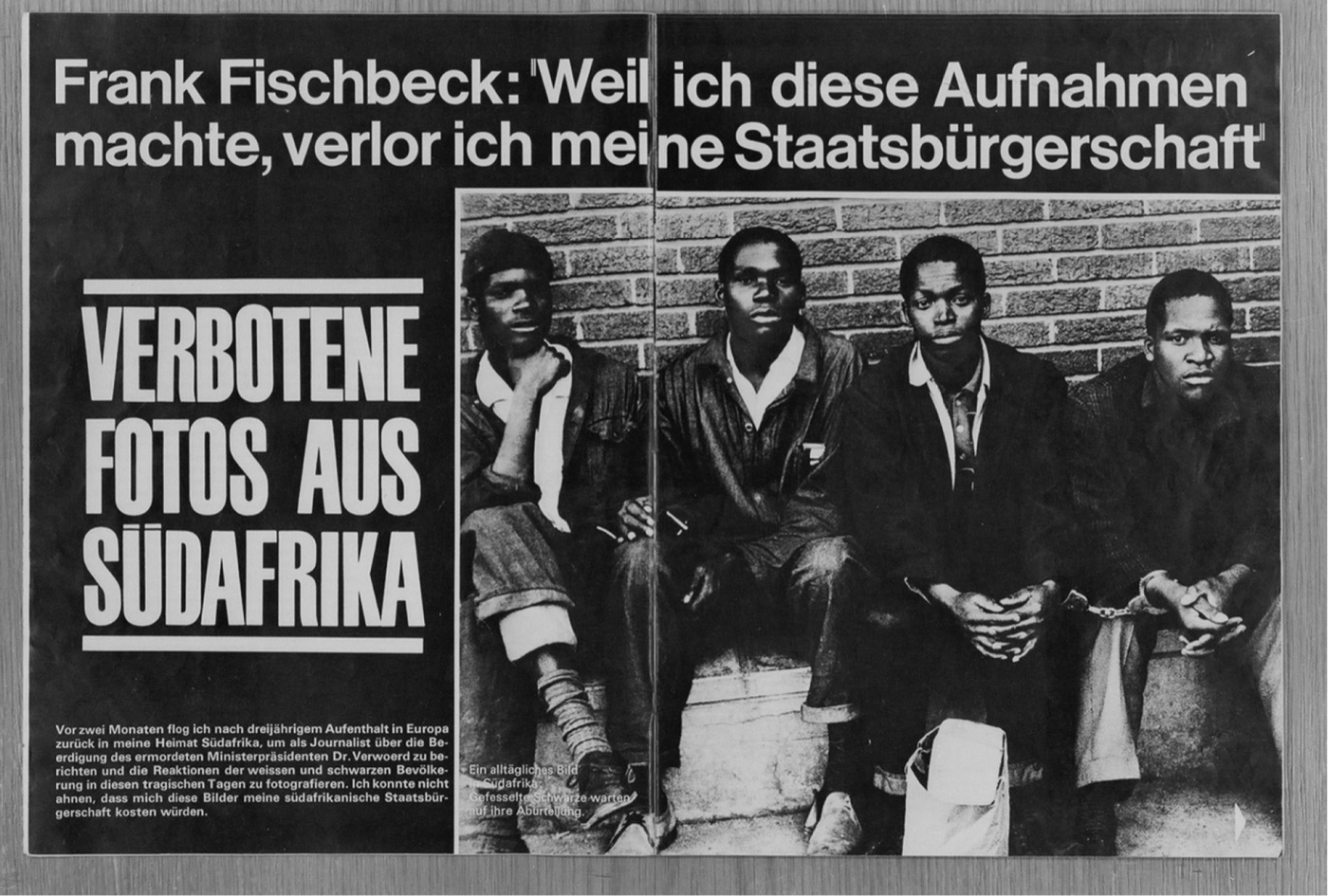

Frank Fischbeck’s life as a photojournalist began in Johannesburg with The Rand Daily Mail, a newspaper staunchly vocal in opposing the government’s stand on racial segregation. It was this anti-apartheid activism that brought Frank into frequent conflict with the governing authorities.

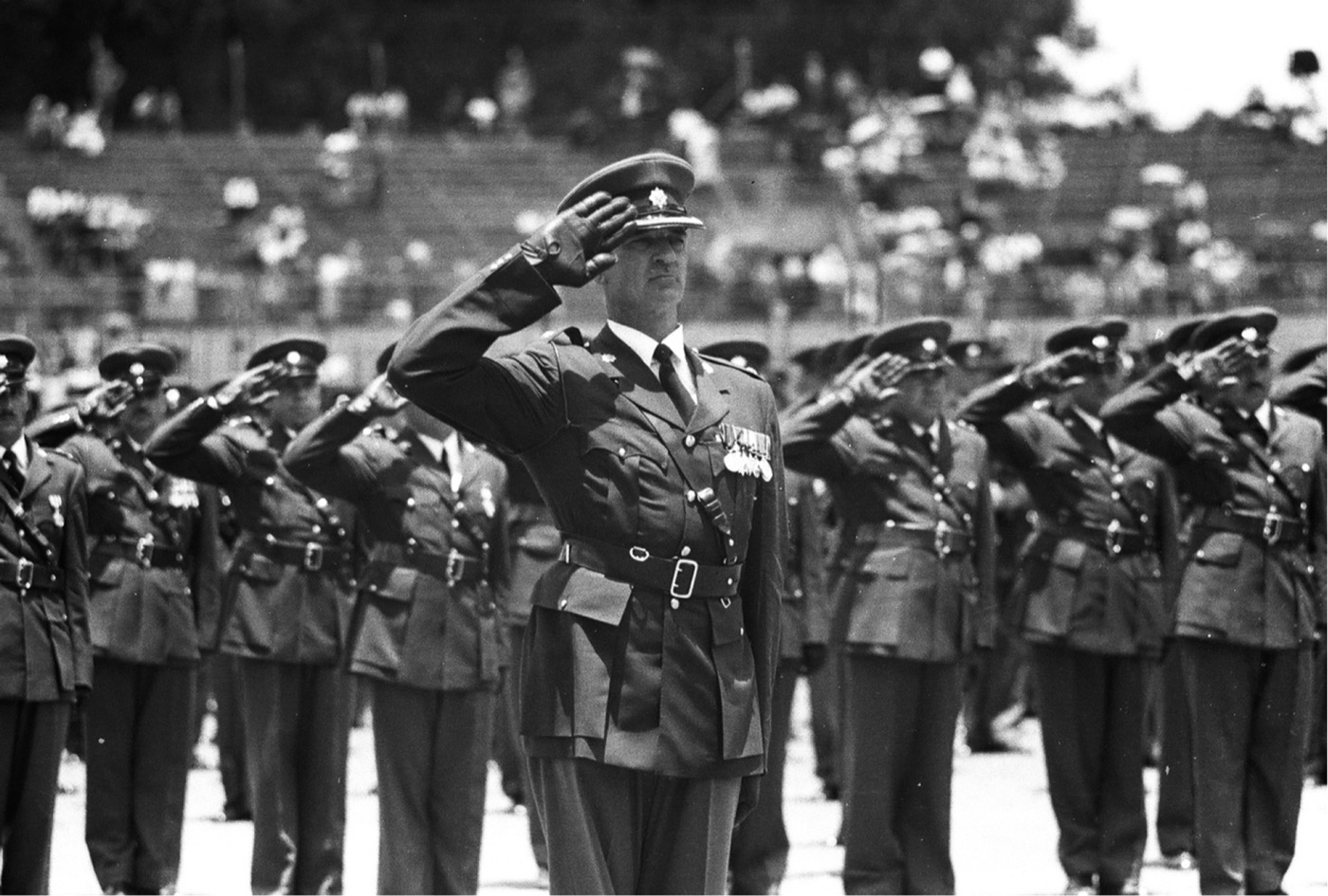

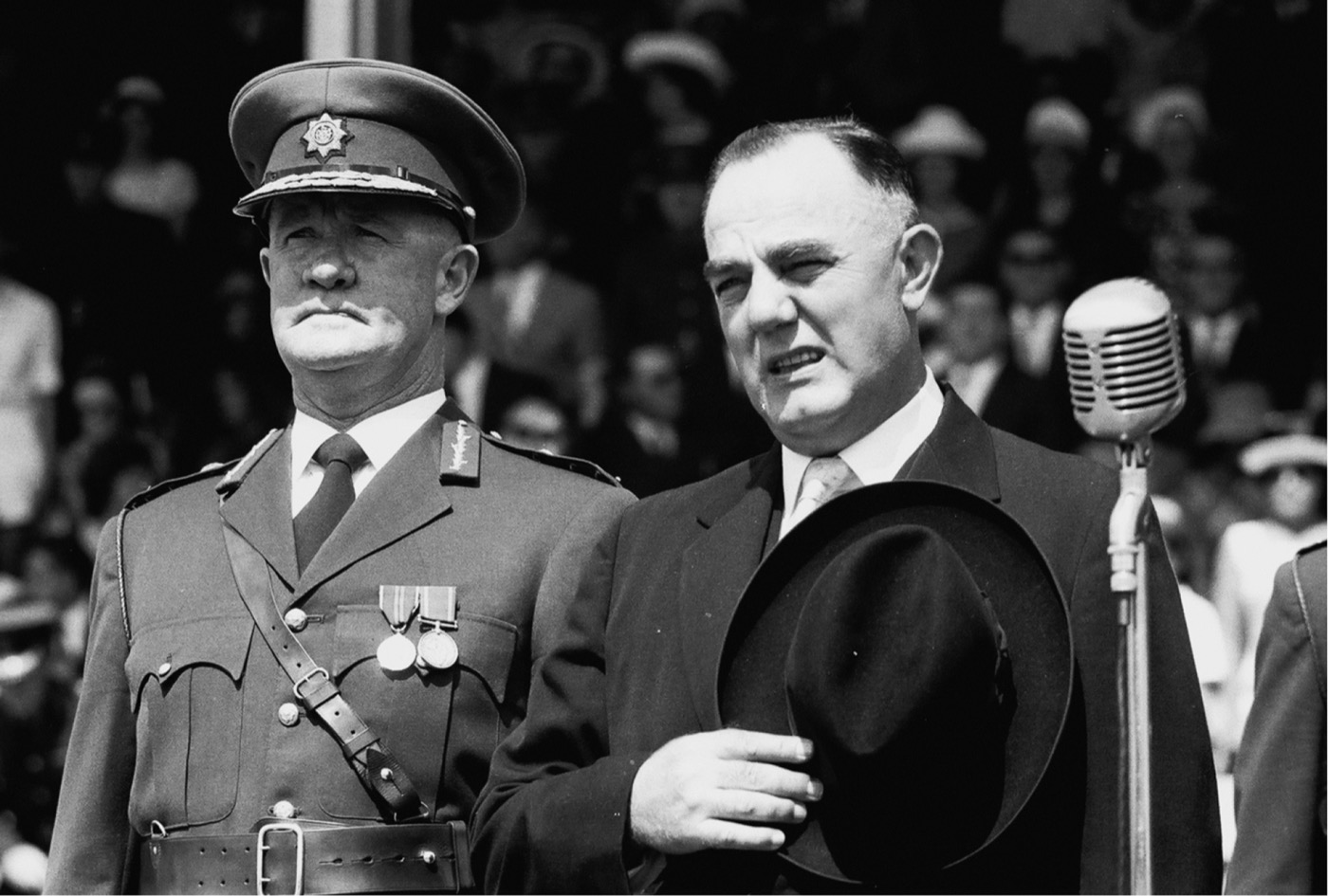

After the Sharpeville massacre in March 1960, Hendrik Verwoerd – the country’s prime minister and a man known as ‘the architect of apartheid’ - tightened his grip on the country. Two attempts on Verwoerd’s life were made, in both cases the perpetrators were white South Africans. The second - and fatal - attack in September 1966 in the House of Assembly in Cape Town was by a Greek immigrant who considered the prime minister a dictator and tyrant.

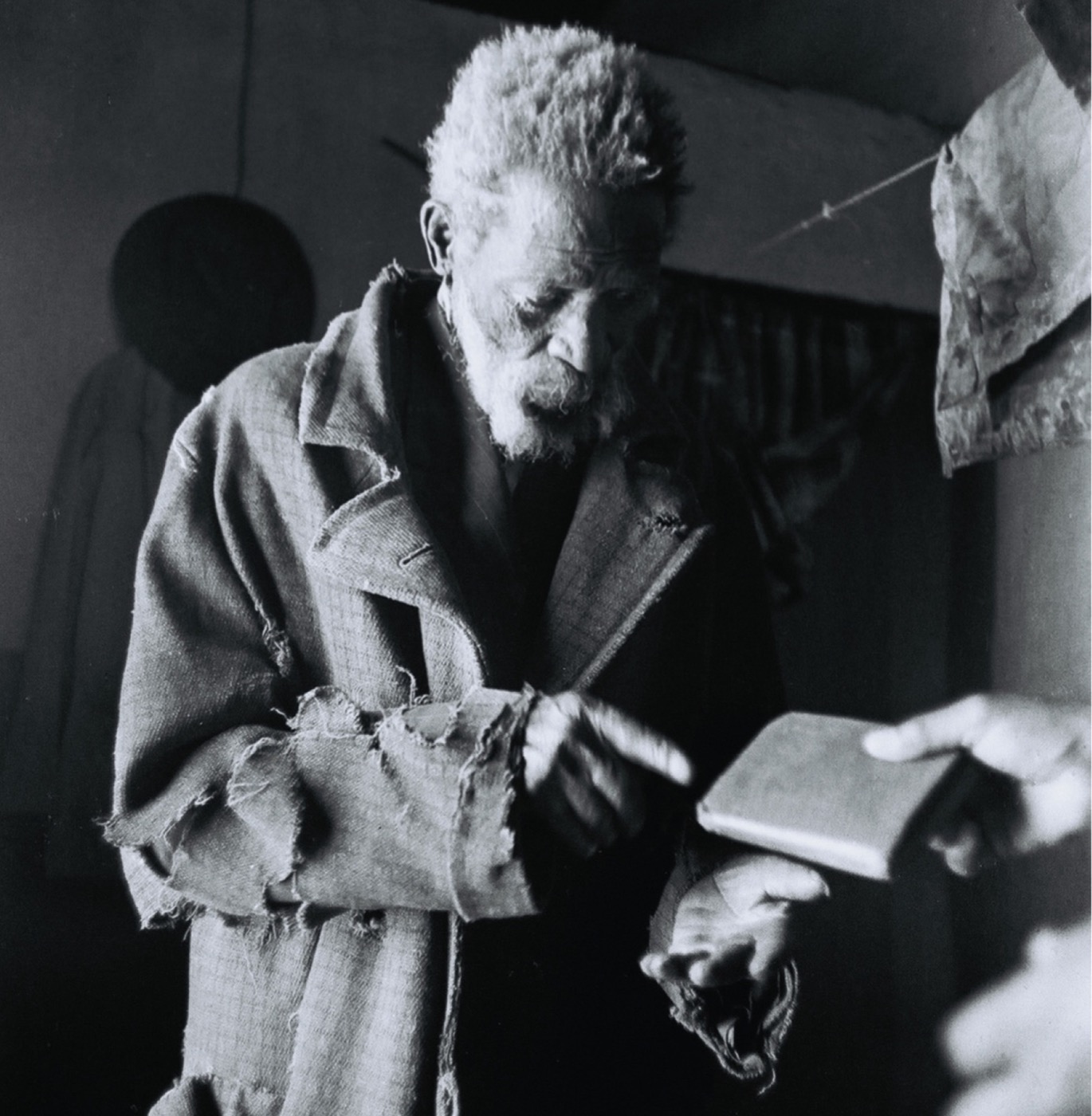

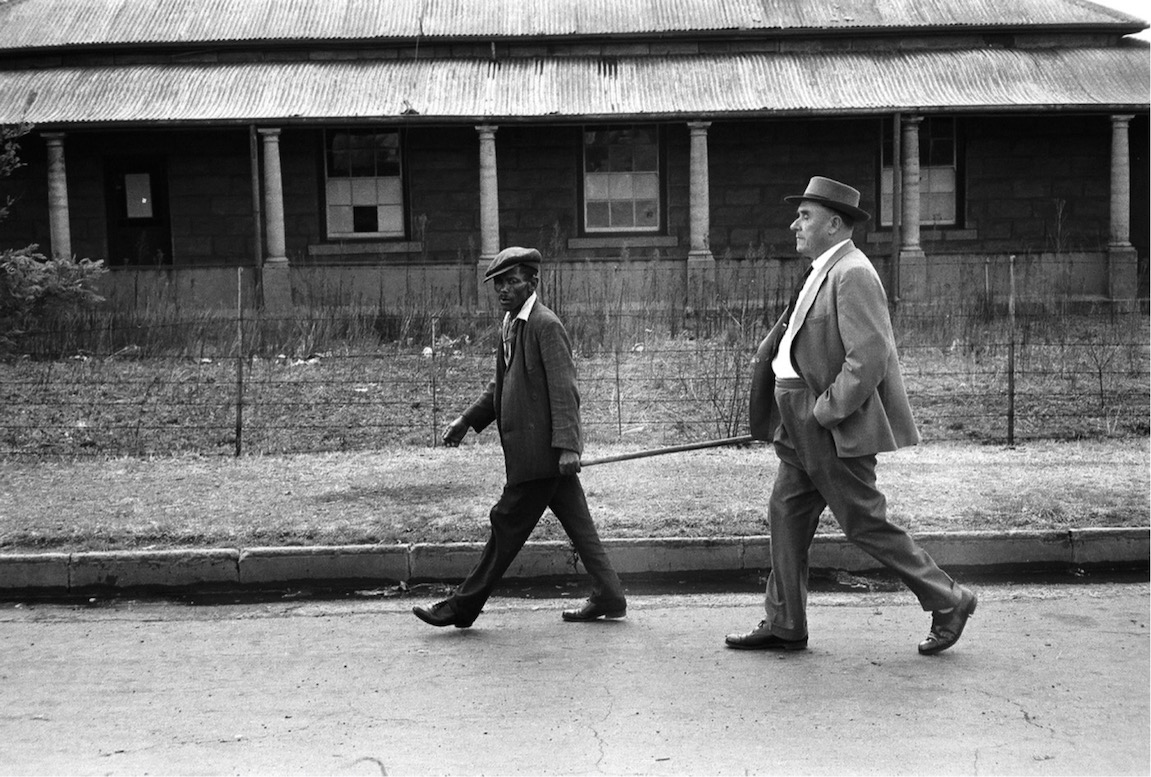

During the tense days that followed Verwoerd’s funeral, Frank continued to document the mood in South Africa between blacks and whites. In one instance at the Johannesburg railway station, he photographed shackled black labourers who were being sent off to labour camps. Those railway photos set in motion a swift train of events that changed the course of Frank’s life. On storming his car, the police confiscated his remaining cameras, film and hand-written notes, assuming they had secured the incriminating evidence of convicting him of contravening the “Prisons Act”.